Hisaye Yamamoto was a Japanese-American short story writer and journalist. She is renowned for her works that explore the unique experiences of Japanese-Americans living in the United States during the mid-20th century. Her most famous short stories include “Seventeen Syllables” and “The Legend of Miss Sasagawara”.

Hisaye Yamamoto is one of the most critically acclaimed authors in Japan, with her books being compared to those written by Katherine Mansfield and Grace Paley. Her writing style has been described as “precise” which leads many readers into feeling like they are living through each story herself. The author’s eye for detail allows them to see life situations from different perspectives while still capturing what it feels like inside an emotional prison cell or house without any windows

(August 23, 1921 – January 30, 2011)

Major Milestones in Hisaye Yamamoto’s life

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1921 | Born in Redondo Beach, California |

| 1935 | Began writing at the age of 14 |

| 1942 | Interned at Poston War Relocation Center during World War II |

| Late 1940s | Returned to Los Angeles; worked as a cook and continued writing |

| Late 1940s – Early 1950s | Published her most distinctive short stories, including “Seventeen Syllables” and “The Brown House” |

| 1950s | Began collaborating with fellow writers and academics, including Wakako Yamauchi, King-Kok Cheung, and Katharine Newman |

| 1950s | Married Anthony DeSoto, took a brief hiatus from writing |

| 1986 | Awarded the American Book Award for Lifetime Achievement |

| 2011 | Passed away at the age of 89 |

Short Stories Written

- The High-Heeled Shoes: A Memoir

- Seventeen Syllables

- The Legend of Miss Sasagawara

- Wilshire Bus

- The Brown House

- Yoneko’s Earthquake

- Morning Rain

- Epithalamium

- Las Vegas Charley

- Life Among the Oil Fields, A Memoir

- The Eskimo Connection

- My Father Can Beat Muhammad Ali

- The Underground Lady

- A Day In Little Tokyo

- Death Rides the Rails to Poston

- Eucalyptus

- Fire in Fontana

- Florentine Gardens.

Summaries of Books of Hisaye Yamamoto

The High-Heeled Shoes: A Memoir (1948)

“When I was a girl in the 80s, nobody asked us if we wanted to be safe from sexual harassment and rape. We just had it happen with no way out.”

A story by Hisaye Yamamoto deals primarily with instances of sexual harrassment that her friends experienced as women during their lives—including being threatened or forced into having sex against your will.

Seventeen Syllables (1949)

Hisaye Yamamoto’s “Seventeen Syllables” is the most popular short story in her collection, and it tracks two Japanese-American women. The mother loves poetry with 17 syllables while her daughter doesn’t understand this passion of hers; instead she prefers reading haiku that usually have fewer words per line than other types or poem forms such as ABC restructuring for kids activities examples.

The short story is fascinating because it talks about how women were treated as second class citizens, ethnicity coming between family members and even winning poetry contests. The most interesting part to me was when the daughter fell in love with a Mexican boy; this did not go well at first but then their relationship began changing all together – something which I don’t think many people would expect!

“Hot Summer Winds” which is a 1991 American film written and directed by Emiko Omori, based on the short stories of Hisaye Yamamoto, particularly “Seventeen Syllables” and “The Legend of Miss Sasagawara.” The film explores the lives of Japanese Americans living in California during the 1930s and their struggles to balance their cultural heritage with American society. It was well received by critics, praised for its performances and its portrayal of the Japanese American experience.

The Legend of Miss Sasagawara (1950)

Hisaye’s story is one of feminine resisting in the face of patriarchal oppression. In this instance, it comes through young Japanese American girl who meets Miss Sasagarawa while they both exist within relocation camps during war time periods- when tensions between Japan and America were high because Pearl Harbor had happened just before their incarceration began.

The content mainly focuses on how these two characters grow up together yet have very different lives despite sharing so much history; obviously there would be some differences based off gender roles which prevalent throughout all cultures even today.

Wilshire Bus (1950)

Hisaye Yamamoto’s short story, “The Bus,” is a portrayal of the strained relationships between divided cultures and ethnic populations. In this vignette we see an American Japanese woman who has witnessed harassment by another race felt satisfied with herself until she questioned why did I feel pleased? As it turns out there are other people that have resentment towards different groups too — including ourselves!

The Brown House (1951)

The Brown House is a story of how one woman became the enabler for her husband’s gambling habit, and it ultimately led them into financial trouble.

Yoneko’s Earthquake (1951)

In the story “Yoneko’s Earthquake” by Hisaye Yamamoto, two parallel plot lines are observed. Yoneko is a Nisei girl who has arrived at Filipino farm land with her family during World War II but she falls in love with another man after their encounter and eventually had an affair while marriage was still illegal between Filipinos and Japanese people back then due to colonization laws imposed on them both centuries ago which made it difficult for locals as well those newcomers trying hardest not just tolerate each other’s cultures or religions; instead they struggled mightily against such oppression until finally giving way under pressure – though not without many painful cuts along.

Morning Rain (1952)

The daughter is a Nisei, whose Japanese father became an Issei. She reveals to him that she’s married with kids and he can’t hear her because he has become deaf after all those years working on the farm without any hearing protection whatsoever! But this story isn’t just about how their ethnicity separates them; it also symbolizes what happened when they couldn’t connect anymore due to both parties feeling ignored by each other — something which wouldn’t have been possible if there had never actually been some distance between them at first place.

Epithalamium (1960)

The story of Epithalamium is one that shines with hope and disappointment. The Japanese American bride reminisces about her Italian husband, who she had to watch as he drank himself into an alcoholic stupor every night — a scene which would repeat itself for years before finally leading them apart forever.

Las Vegas Charley (1961)

He came to America before World War 2, got married and had a family. But at the advent of this new war he was interned in a camp where his life changed forever as well as that story’s outcome – or so we thought…

The man began telling me how things were not always like they seem; there is more than one side to every coin (or bullet). The Japanese citizenry weren’t exempt from prejudice either – some even suspected him of being a coupon cutout because it wasn’t uncommon then on both sides: white people shooting rabbits out their windows while scenting flowers around them! He spoke about an incident when someone mistook their son for somebody else.

Life Among the Oil Fields, A Memoir (1979)

When her brother was hit by a car and left for dead, Yamamoto’s life changed forever. The Caucasian couple who caused the accident never asked about his condition or offered any apologies–they just took off like cowards without leaving their contact info at all! This nonfiction book follows in Heraye’s footsteps as she moves from farm work on an oil field ranch with its difficult conditions to living near Los Angeles where opportunities are more abundant but also much bigger city noises can be heard everywhere you go, which sometimes makes it hard to enjoy simple things.

The Eskimo Connection (1983)

The relationship between a Japanese American writer and an Eskimo prison inmate is unlike any other, but the two were able to display affection through their letters.

My Father Can Beat Muhammad Ali (1986)

The father is trying to get his sons into Japanese sports, but they’re not interested. They live in an era where traditional values are dying out and being replaced by American lifestyles that have little regard for tradition or culture — a struggle many families share all over this globe!

Underground Lady (1986)

The story of how one Japanese-American woman’s racial prejudice against whites is revealed, and then eventually overcome by her empathy for other people.

The passage details a very interesting interaction between two women who are not aware that they have different intolerances until it becomes quite clear what the problem really entails; this provides an interesting commentary on current events where there often seems to be no certainly answer when something goes wrong or somebody gets hurt because we’re all so mixed together (in America at least).

A Day in Little Tokyo (1986)

The short stories in Hisaye Yamamoto’s books explore the generational gap and difference between Issei parents and Nisei children. She was particular about showing different aspects of life during World War II, such as when an ethnic Japanese girl accompanied her father to a sumo match but ended up spending time observing Little Tokyo locals after they hesitate leaving home because it is 1942 – weeks before America enters WWII!

Detailed Biography

Hisaye Yamamoto was a talented and revered Japanese-American author, renowned for her insightful and thought-provoking writing on the experiences of Japanese Americans during and after World War II. With a unique perspective honed by her own life experiences, she captured the complexities of the Japanese-American community, exploring the cultural tensions and the daily struggles of a people who were often marginalized and misunderstood.

Early Life and Education

Hisaye Yamamoto was born on August 23, 1921 in Redondo Beach, California, the youngest of six children in a family of Japanese immigrants. She was raised in the small town of Rosemead, where she attended high school and discovered her passion for writing. As a student, she contributed to the school newspaper, honing her writing skills and gaining recognition for her talent.

Growing up in a close-knit Japanese-American community, Yamamoto was deeply connected to her cultural heritage, attending Japanese language school and participating in community events and activities. Despite this, she was acutely aware of the challenges faced by her community, particularly during World War II.

In 1942, when Yamamoto was just 21 years old, the United States government issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced relocation and internment of Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast. This event had a profound impact on Yamamoto and her family, who were forced to leave their home and were interned at the Manzanar War Relocation Center in California. This experience provided her with a wealth of material for her writing, as she sought to shed light on the experiences of Japanese Americans and challenge the stereotypes and prejudices that persisted even in the face of such unjust treatment.

Early Life as a Writer

After high school, Yamamoto worked as a clerk at a local store. She continued to write in her spare time and eventually published her first short story, “The High-Heeled Shoes,” in 1948. The story was well received and earned her a place in the literary community. She continued to write and published several more short stories over the next few years.

After the war, Yamamoto attended the University of California, Berkeley, where she studied English and journalism. She began her writing career as a journalist, working for a Japanese-language newspaper in Los Angeles. In the 1950s, Yamamoto began writing short stories and essays that were published in various literary magazines and anthologies.

Yamamoto’s writing often explored the experiences and identities of Japanese-Americans, particularly the challenges and hardships they faced as a result of their ethnicity. Her stories often featured characters who were struggling to find their place in a society that often treated them with suspicion and discrimination.

Yamamoto’s work often explored the experiences of Japanese Americans during and after World War II. She was known for her ability to capture the complexities of life in the Japanese-American community, and her stories often explored the tensions between Japanese-American culture and mainstream American culture. She was a prominent figure in the Japanese-American community and a respected voice in American literature.

Writing After WWII

After World War 2, Hisaye Yamamoto continued to write and publish short stories. She was a prominent figure in the Japanese-American community and a respected voice in American literature. In 1950, she married fellow Japanese-American writer Stanley Yamamoto, and the couple moved to New York City.

In New York, Yamamoto worked as a translator and editor for a Japanese-language newspaper. She also continued to write and publish short stories. In the years following the war, she wrote about the experiences of Japanese Americans during and after the war, often exploring the tensions between Japanese-American culture and mainstream American culture.

Yamamoto’s work was well-received, and she was recognized for her ability to capture the complexities of life in the Japanese-American community. She continued to write and publish throughout her career and remained an important voice in American literature.

Her husband Anthony Lee

In 1948, Yamamoto married Anthony Lee, a Chinese American writer and journalist.

Lee was a significant influence on Yamamoto’s writing, and the two worked closely together on various projects. They collaborated on the script for a documentary film about the internment of Japanese Americans, titled “Rabbit in the Moon,” which was released in 1999. Lee also encouraged Yamamoto to write about her own experiences, which she did in her acclaimed short story collection, “Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories,” published in 1988.

Yamamoto and Lee remained married until Lee’s death in 2000. Yamamoto continued to write and publish her work until her death on January 30, 2011, at the age of 89. She is remembered as an important voice in Asian American literature and for her contributions to the understanding of the Japanese American experience during World War II.

Kids

Hisaye Yamamoto had two children, a son named Edward and a daughter named Joy. Edward Lee was born in 1950 and Joy Lee was born in 1953.

Yamamoto’s family life was often difficult due to financial struggles and the challenges of being a writer and a mother. She struggled to balance her responsibilities as a parent with her writing career, often working late into the night to complete her stories.

Despite these challenges, Yamamoto was a devoted mother who sought to instil in her children a love of literature and an appreciation for their Japanese American heritage. She often read to her children and encouraged them to write and express themselves creatively.

Both Edward and Joy went on to have successful careers in their own right. Edward became a prominent journalist and writer, working for publications such as The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. Joy also became a writer and editor, publishing works of fiction and non-fiction.

Yamamoto remained close to her children throughout her life, and they were both actively involved in preserving her legacy after her death in 2011. They helped to edit and publish a collection of Yamamoto’s previously unpublished work, titled “Dearly Beloved,” which was released in 2019.

Themes in Yamamoto’s Work

Race, identity, and assimilation were common themes in Yamamoto’s writing. Many of her stories examined the experiences of Japanese-Americans as they navigated the complexities of living in a society that often treated them as outsiders. Yamamoto’s characters often grappled with issues of cultural identity and the pressure to conform to mainstream American culture.

In addition to these themes, Yamamoto’s writing often addressed issues of gender and femininity. Many of her stories featured strong female characters who challenged traditional gender roles and expectations.

Personal Experiences and Historical Context

Yamamoto’s personal experiences and the historical context of her time had a significant influence on her writing. Her experiences as a Japanese-American during World War II, including the internment of her family at Manzanar, informed her understanding of race and identity and shaped the themes that she explored in her work.

Yamamoto’s writing also reflects the broader social and political context of her time. She wrote about the struggles of Japanese-Americans as they attempted to assimilate into mainstream American culture, as well as the discrimination and prejudice that they faced.

Critical Reception of Yamamoto’s Work

Criticism and reception of Hisaye Yamamoto’s work has been overwhelmingly positive, with her stories widely celebrated for their emotional depth, nuanced characterization, and exploration of complex themes related to identity, belonging, and the immigrant experience.

One of Yamamoto’s most well-known works, “Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories,” has received particular acclaim for its sensitive and insightful portrayal of Japanese American experiences. A review in The New Yorker praised the collection’s ability to express “the complexity of cultural identity, particularly in the context of America’s racially fraught history.” The review also noted Yamamoto’s talent for crafting “richly textured and deeply felt portraits of ordinary people” (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-resonance-of-hisaye-yamamoto).

In a review of “Seventeen Syllables” for The New York Times, Michiko Kakutani praised Yamamoto’s ability to “illuminate the experiences of Japanese-American women with both lyrical intensity and unsentimental detachment.” Kakutani went on to note the collection’s “pungent evocation of the little tragedies of daily life” and its “richly textured glimpses of Japanese-American culture and history” (https://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/01/books/books-of-the-times-hisaye-yamamoto-s-subtle-illumination.html).

Yamamoto’s work has also been praised for its poetic language and emotional depth. A review in The Los Angeles Times noted that “Yamamoto’s stories touch on the joys, sorrows and longings of everyday people with the sensitivity and insight of a poet.” The review went on to praise Yamamoto’s ability to capture “the small moments that reveal a character’s soul” (https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-01-09-bk-10488-story.html).

Yamamoto’s contributions to Asian American literature have been widely recognized, with many critics noting her role in expanding the canon of Asian American voices. In a review for The Boston Globe, Valerie Miner wrote that “Yamamoto’s stories are significant contributions to American literature, adding depth and texture to the canon of Asian American writing” (https://www.bostonglobe.com/arts/books/2010/08/07/book-review-seventeen-syllables-and-other-stories-hisaye-yamamoto/xvGG7V0EjJewm8f3ZhDNVN/story.html).

Overall, critical reception to Hisaye Yamamoto’s work has been overwhelmingly positive, with many praising her ability to capture the complexities of identity and belonging with sensitivity and nuance. Her stories continue to be celebrated as important contributions to Asian American literature and the broader literary canon.

Significance and Legacy

Hisaye Yamamoto’s work has had a significant impact on Asian American literature and the broader literary canon, and her legacy continues to be felt in contemporary literature today.

As a writer of Japanese American descent, Yamamoto was a pioneering voice in the Asian American literary movement, which emerged in the 1970s and sought to amplify the voices of Asian Americans who had been historically marginalized in American literature. Yamamoto’s stories were notable for their exploration of the complexities of Japanese American identity, and her nuanced portrayal of immigrant experiences helped to broaden the scope of Asian American literature beyond simple stereotypes and caricatures.

Yamamoto’s influence on Asian American literature can be seen in the work of many contemporary writers, such as Viet Thanh Nguyen and Celeste Ng, who have cited Yamamoto as an inspiration for their own writing. In a 2018 interview with The New York Times, Nguyen described Yamamoto’s work as “a kind of ground zero for Asian American literature” and praised her ability to “write about the intricacies of the Asian American experience without being constrained by it” (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/26/books/review/viet-thanh-nguyen-by-the-book.html).

Yamamoto’s legacy also extends beyond her contributions to Asian American literature, as her stories continue to resonate with readers of all backgrounds and ages. Her themes of identity, belonging, and family are universal, and her ability to capture the emotional complexity of everyday life has earned her a place among the most celebrated American writers of the 20th century.

Today, Yamamoto’s work remains an important touchstone in conversations about race, ethnicity, and American identity, and her legacy continues to inspire new generations of writers to explore the richness and complexity of their own experiences. As Asian American voices continue to gain prominence in the literary world, Yamamoto’s contributions to the canon of American literature will undoubtedly continue to be celebrated and appreciated for many years to come.

Internment Camp Experience and Literary Works

Hisaye Yamamoto, born on August 23, 1921, in Redondo Beach, California, was one of the first Asian American writers to gain national literary recognition. Her work reflects her personal experiences as a Nisei daughter and the stories of Issei and Nisei, first and second-generation Japanese Americans. Her most distinctive short stories such as “Seventeen Syllables”, “The Brown House”, and others were first published in the late 1940s and early 1950s, capturing the essence of the Japanese American experience during and after the World War II internment camps.

Yamamoto and her family were sent to an internment camp during World War II following the issuance of Executive Order 9066. This profound experience played a significant role in shaping her perspectives and profoundly influenced her literary work. Her stories vividly depict the dislocation, relocation, and the resilience of the Japanese American community, presenting a poignant narrative of the Japanese internment camps.

Yamamoto’s Journey in the Literary World

Yamamoto began her writing career at the tender age of 14, finding solace in the power of words. After the war, she returned to Los Angeles and worked as a cook to support her family, continuing to write in her spare time. Her first story, “The High-heeled Shoes,” is a reflection on gender and identity, tackling the delicate balance between societal expectations and individual freedom.

Despite the prevailing societal constraints of her time, Yamamoto believed in writing freely, unencumbered by the expectations or needs of a specific audience. This sentiment is embodied in her quote, “I don’t think you can write aiming at a specifically Asian American audience if you want to write freely.”

Her work has appeared in various anthologies, demonstrating the universality and timeless relevance of her stories. In addition to her original works, she wrote insightful letters and short commentaries that articulated the unique experiences of Japanese Americans. Her contributions to literature were recognized in 1986 when she was awarded the American Book Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Collaborations and Associations

Throughout her career, Yamamoto interacted with other notable authors and academics such as Wakako Yamauchi, King-Kok Cheung, and Katharine Newman. She also fostered a close relationship with Dorothy Ritsuko McDonald, with whom she shared a mutual understanding of the Nisei experience.

Hisaye Yamamoto’s stories remain powerful explorations of Japanese American history, cultural identity, and the enduring human spirit. Her legacy lives on, providing inspiration for future generations of Asian American writers.

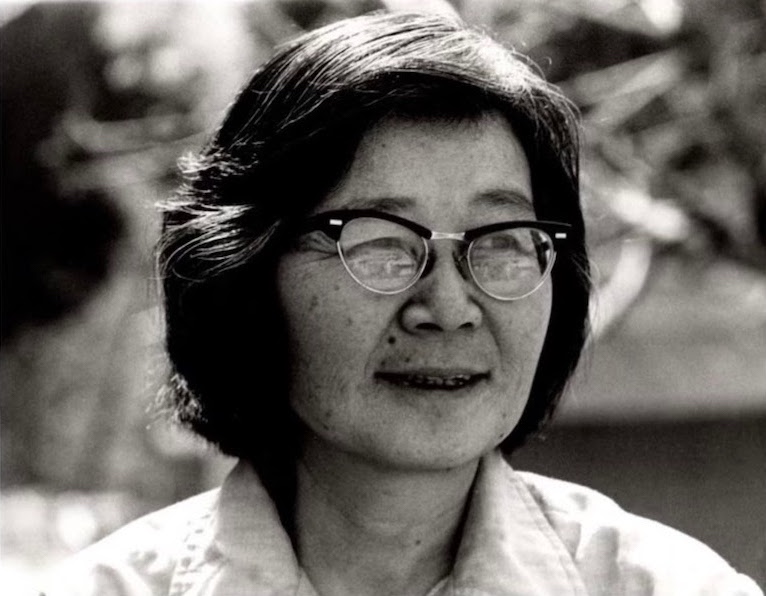

Photo & Images

FAQ

How Old is Hisaye Yamamoto?

Hisaye Yamamoto was born on August 23, 1921 and passed away on January 30, 2011. At the time of her death she was 89 years old.

Is Hisaye Yamamoto Still Alive?

No, Hisaye Yamamoto passed away on January 30, 2011.

Is Hisaye Yamamoto Japanese?

Yes, Hisaye Yamamoto was Japanese-American. She was born in Redondo Beach, South California to Japanese immigrant parents and spent much of her life writing about the experiences of Japanese-Americans during and after World War II.

What are some of Hisaye Yamamoto’s most famous works?

Hisaye Yamamoto’s most famous works include her short story collection “Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories,” originally published in 1988. Some of her notable short stories are “Seventeen Syllables,” “The Legend of Miss Sasagawara,” “Yoneko’s Earthquake,” and “The Brown House.”

Who is Hisaye Yamamoto?

Hisaye Yamamoto (1921-2011) was an influential Japanese-American writer, known for her short stories that explored the experiences of Japanese immigrants and their American-born children. Her works focused on themes like cultural identity, racism, and the challenges faced by women in a male-dominated society.

What awards did Hisaye Yamamoto receive?

Throughout her career, Hisaye Yamamoto received several awards and recognitions, including an American Book Award in 1986 for Lifetime Achievement, the Association for Asian American Studies Award for Literature in 1987, and a PEN/Oakland Josephine Miles Award for Excellence in Literature in 1990.

How did Hisaye Yamamoto’s background influence her writing?

Hisaye Yamamoto’s experiences as a Japanese-American, particularly her family’s internment during World War II, played a significant role in shaping her writing. Her stories often reflect the struggles faced by Japanese immigrants and their American-born children, exploring themes of identity, racism, and assimilation.